The Middle Line

Works

Arists

Vanja Pagar (Croatia, 1969) / Etel Adnan (Lebanon, 1925)

Ana Arcas (Spain, 1983) / João Queiroz (Portugal, 1957)

Dare Dovidjenko (Croatia, 1949) / Daniel Gustav Cramer (Germany, 1975)

Sandra Gamarra (Peru, 1972) / Geert Goiris (Belgium, 1971)

Josh Begley (United States, 1984) / Olafur Eliasson (Denmark, 1967)

Text

The Middle Line

For its eighth exhibition in Madrid, LiMac brings together the works of 11 artists around the notion of the horizon that we have inherited from western landscape painting.

The naturalization of this genre extended concepts that have determined our relationship with our environment. To this day, landscapes still serve as a mean to understand the “outside” that, as they bring us closer, also create a distance.

Through this line, depth and proximity are juxtaposed. The outer world is reduced and fragmented into planes, with its own logics and priorities. During the centuries of colonization, the paintings of exotic landscapes served as a tool of symbolic territorial conquest that, in parallel with the European rural exodus to the cities and the subsequent expropriation of the lands in the hands in power, displaced human beings from its ancestral environment. The landscape is always broad and inhabited, open and ready to be organized by the western man. Today, the ecological disasters and territorial tensions are a symptom of how we relate to the place we inhabit.

The horizon orders top and bottom, the sky and the earth, emptiness and fullness. It appears as a line that surrounds sight and places each element. Nonetheless, the horizon only exists in the gaze; it is an illusion that, just like borders, conditions the territory. Similar to a frame that contains a painting, the horizon organizes the “natural disorder” continuously and permanently.

The Middle Line, presents five paintings from the Relations series, where Vanja Pagar (Croatia, 1969) stripes down the essence of landscapes by juxtaposing two color planes in a rectangular format so to represent the horizon of the sea at different times of the day. In a direct dialogue with the color studies of the impressionists and Josef Albers, the artist creates parallels with the minimalism of Blinky Palermo.

The work of the acclaimed artist and poet Etel Adnan (Lebanon, 1925) links abstraction and figuration within the landscape. In a painting of the Tamalpais Mountain in San Francisco, that Adnan painted numerous times, as Cézanne painted Mount Saint Victoire (1), the use of vibrant colors are reminiscent of naive art landscapes, and, like Adnan, celebrate life and nature as a whole.

As we observe two miniature paintings of Ana Arcas (Spain, 1983), the reduction of nature becomes tangible. In her work Peter Doing in Lima, Arcas captures the immensity of the sea with a horizon blurred by mist and a minimal brushstroke that situates a boat in the middle of the Pacific. In Let the Color of the Sea not Know What does the One of the Sky the fog of the Peruvian coast calibrates the elements of the landscape in a similar tone.

The brushstrokes of the recent encaustic paintings by João Queiroz (Portugal, 1957) generate a circular space. In this work, the profile of the earth and the sky are bathed in a halo of light. The movement of the painting delineates the changing relief of the horizon.

In the diptych How is it?, the Peruvian resident Dare Dovidjenko (Croatia, 1949) questions how to look at the Pachacamac ruins in the sandy terrain of Lima´s coast. Each painting represents the same scene but one of them has been hung upside down. In this inversion of the horizon, humor serves as a key to dissolve conventions and show the surreal side of the landscape.

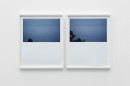

The desert photographed by Daniel Gustav Cramer (Germany, 1975) in the large format work Untitled (Sands) III captures the vibrations of the wind and the earth as a multitude of lines form a parallel and wavy rhythm. The point of view does not allow to distinguish the horizon but the lines create an optic game that seems infinite. In another work by the artist, a photographic diptych from his Tales series, that combines scenes of travels, sometimes just separated by seconds, a relation establishes itself with the fragment and the continuity of a possible narrative of landscape.

The tension between the horizon and its representation manifests itself in There Are no Straight Lines in Nature where Sandra Gamarra (Peru, 1972) appropriates several classic landscapes to paint or glue them on mirror plinths. Different lines of horizon intersect and each work expands their frame. Through this illusion, Gamarra questions the format and the structure of landscapes and puts bidimensionality into a sculptural form.

Capturing an explosion on an apparently quiet lake, the photography Blast#6 by Geert Goiris (Belgium, 1971) interrupts the supposed neutrality of traditional landscape. At this moment, a diffused horizon appears determined by the presence of man.

The painting made by LiMac after Sean Snyder´s (United States, 1972) video work Tableau Bateau (literally Boat Painting) manages to substitute a work whose loan had to be cancelled one week before the opening of this exhibition. Originally made from fragments of sea storms found on the internet that took place at the beginning of the twentieth century until recent years is reproduced on a hacked mobile phone. The liquidity of these maritime scenes relate with the mobility of the image and its format. The storms become the metaphor of the technological changes as well as a symptom of the coming environmental crisis that shows an intangible horizon in permanent undulation.

The horizon changes radically in Josh Begley’s (United States, 1984) video work as it uses a satellites’ point of view. His film Best of Luck With the Wall travels in 6 hypnotic minutes the entire extension of the Mexican and United States border. The artist stitched more tan 220.000 images from Google Maps in which the borders’ is read as a socio-political horizon. Best of Luck… was produced by the journalist Laura Poitras (author of the documentary Citizen Four about Edward Snowden) and Andy Moor, from the seminal anarchist post-punk band The Ex, composed its soundtrack.

Another change of perspective is observed in the photogravure Cartographic Series III by Olafur Eliasson (Denmark, 1967) made from high definition satellite photography that the artist bought from the NASA. It shows how our way to see and understand the world and our horizon is mediated and determined by technological advances.

In this journey through deserts, seas, forests and skies we can see the horizon transform itself from a determined and rational state to another one that is multiple and ambivalent. The middle line falls apart, ripples and regenerates. It is not the line that organizes the world, but one that alters the assumed world.

Antoine Henry Jonquères

(1) Laura Herman, “Hans Ulrich Obrist”, TLmag 25 extended, Jul 8, 2016, http://tlmagazine.com/hans-ulrich-obrist/